Recreation

Maine’s environment and landscapes provide many opportunities for recreation; from rock hounding (mineral collecting), hiking, boating of all kinds, swimming, fishing, skiing, bird watching, gardening and much more.

Maine’s environment and landscapes provide many opportunities for recreation; from rock hounding (mineral collecting), hiking, boating of all kinds, swimming, fishing, skiing, bird watching, gardening and much more.

Common Name: Dragonfly

About:

Habitat: low lying wetlands; may also occur in mountainous regions

Food: Almost exclusively carnivores; midges, mosquitos, black flies, butterflies, and moths

Physical Description: Head with compound multifaceted eyes; thorax where four transparent wings are attached; elongated abdomen that is tail-like; colors vary depending on the species, but highly iridescent blues, greens, and yellows are common

Predators: Birds

Dragonflies have been around for nearly 325 million years, some of the earliest examples had wingspans up to 30 inches.

Common Name: Paper Birch, White Birch, Canoe Birch

Bark of White Birch. Photo courtesy of Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Betula papyrifera

About:

A deciduous tree capable of reaching a height up to 120 feet, but only living for an average of 30 to 100 years. The tree may grow as a single trunk. However, in an open landscape it may develop multiple trunks. The tree prefers moist soil. It grows along rivers and streams and the edges of ponds and lakes.

Physical Description:

Leaves: Leaves are 2 to 4 inches in length, dark green, and ovular to triangular in shape.

Bark: The color of the bark changes as the tree matures. It begins as a reddish-brown color when the tree is younger and as the tree ages, the bark becomes bright white with black marks.

Cones: The flower is a slim, cylindrical flower called a catkin.

Uses: The wood from paper birch has a variety of uses including woodenware, clothespins, dowels and spools, firewood, and plywood. The sap from the paper birch has a fairly high sugar content, so it is often tapped and the sap reduced to make a syrup.

The tree gets its name from its white bark which can be used as paper, “paper birch;” it was also used to make canoes, “canoe birch.”

Common Name: Red Spruce

Needles of Red Spruce. Photo courtesy of Keith Kanoti, Maine Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Scientific Name: Picea rubens

About:

Physical Description:

Needles: The leaves are about 0.5 inches long, dark green, and sharply pointed.

Bark: The bark of mature trees is fairly thick and reddish-brown. The bark tends to split apart in irregular shapes giving an overall scaly appearance.

Cones: Cones are 1.5 to 2 inches in length. They start with a dark green color and mature to a light brown.

Uses: A very valuable tree used for building lumber, including joists, sills, rafters, and heavy construction timbers. It is the primary wood used for making paper pulp.

This coniferous tree grows on well-drained soil or rocky upland soil; commonly found on the north side of mountain slopes; and capable of growing 60-80 feet in height.

Cones of Red Spruce. Photo courtesy of Keith Kanoti, Maine Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Common Name: Eastern White Pine

Image Source: Steven Katovich, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Pinus Strobus

About:

The Eastern White Pine occurs in many regions of Maine. It develops best on well-drained and fertile soils. The tree grows rapidly with an average growth height of 1 foot or more each year. It is able to grow for 200 years or more and can become 150 ft high.

Physical Description: It is a type of conifer.

Needles: The needles are 2.5-5 inches long, dark green, and grow in clusters of 5.

Bark: On younger trees the bark is thin and smooth. On matured trees the bark is dark gray to brown and fissured.

Cones: Female and male cones are both produced by an individual tree. Female cones are the larger, up to 8 in in length; they start as a green color and mature to a light brown. Male cones are much smaller and white.

Uses: The wood from the Eastern White Pine is used for interior carpentry and furniture.

Interesting Facts: During colonial times Maine’s logging industry was prolific. The Eastern White Pine was a very important tree during that era and was used for making ship masts. The tree continues to be an important economic resource today.

In 1945 the Maine State Legislature designated the tree as the official tree of the State of Maine. Maine is known as the “Pine Tree State.”

Common Name: American Red Squirrel

red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). Rob Routledge, Sault College, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Tamiasciurus hudsonicus

About:

Habitat: Widely distributed across North America; commonly found near conifers, whether in forested or urban areas

Food: Seeds from conifer cones, other seeds, nuts, mushrooms, small insects, and caterpillars

Physical Description: Smaller sized compared to gray squirrels; larger than chipmunks; reddish fur with white underbelly

Predators: Canadian lynx, bobcat, domestic cats, coyote, owls, hawks, crows, red fox

The front teeth continually grow so that they do not wear down from all the gnawing.

Red squirrel (Tamiasciurus hudsonicus). Steven Katovich, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Common Name: Eastern Chipmunk

Steven Katovich, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Tamias striatus

About:

Habitat: Deciduous forests and areas of thick brush; quite versatile and can be found in many habitats

Food: Grains, nuts, berries, seeds, mushrooms, insects, and other small animals

Physical Description: Reddish-brown fur with white underbelly; distinct black and white stripes along sides extending from neck to tail

Habits: Build complex burrow systems that include dens, tunnels, and food storage areas; breed twice a year in early spring and mid-summer

Predators: Owls, hawks, foxes, and snakes

Common Name: Black-capped Chickadee

Elmer Verhasselt, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Polecile atricapillus

About:

Habitat: Mixed hardwood and coniferous forests; small woodlands and shrubs in residential areas

Food: Insect eggs, beetles, ants, aphids, millipedes, snails, and other small insects; plants including goldenrod, ragweed, wild fruit, seeds of conifers; seeds left in feeders

Physical Description: Light grey backs and tails; black colored head; black bib and white cheeks, gray wings with white highlighted feathers

Habits: named for its call, little or no fear of humans;

The Chickadee is the Maine State Bird. It survives the winter by lowering their body temperatures at night; entering a state of controlled hypothermia (they slow the blood flowing to the parts of their bodies they don’t use while they are sleeping; this helps them save much-needed energy).

Common Name: Bald Eagle

Terry L Spivey, Terry Spivey Photography, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Haliaeetus leucocephalus

About:

Habitat: Nests atop tall trees; prefer to live near water where fish are plentiful, such as rivers, lakes, and coastlines

Food: Primarily a fish eater; will also eat a variety of small mammals

Physical Description: Dark brown feathers for the body and wings, white feathers for head of mature bird (3rd year), neck, and tail; yellow beak and feet

There are only two types of eagles native to North America, Bald Eagles and Golden Eagles. Bald Eagles have an average wingspan of 6 to 8 feet.

Common Name: Red Fox

Ronald Laubenstein, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Bugwood.org

Scientific Name: Vulpes vulpes

About:

Habitat: Variety of different habitats including forest, mountainous regions, and open fields

Food: Seasonal variations in diet; small rodents and other small to mid-sized mammals eaten year round; during spring, summer, and fall months will eat grasses, birds, bird eggs, fruit, insects, and apples; during winter months diet consists mostly of animals

Physical Description: light reddish-orange coat with light gray underside; black paws and tail tip.

Common Name: Porcupine

Scientific Name: Erethizon dorsatum

About:

Habitat: Generally found in coniferous forests but may be found in mixed deciduous woods.

Food: Porcupines are herbivores and their diet varies from winter to summer based on food availability. They forage on clover, acorns, seeds, and tree leaves, buds, roots and twigs in the spring, summer, and fall. In the winter, they forage on conifer needles, the barks of trees like beech, birch, elm, aspen, oak, and a variety of conifers like spruce, hemlock, pine, and fir.

Physical Description: Brown and black with quills covering the tail.

Predators: Natural predators of the porcupine include coyotes, owls, golden eagles, and fishers.

Despite the popular rumor, the quills of a porcupine cannot be ejected. They are designed to release when they come into contact with another animal.

Common Name: Snowshoe Hare

Snowshoe Hare in summer coat. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

About:

Habitat: Forest dwellers that prefer brushy undergrowth.

Food: During the summer, their diet consists of greens, succulent plants, grasses, and ferns. During the winter months, they resort to eating woody vegetation, preferring maple, aspen, birch, and willow.

Physical Description: Appearance varies seasonally. In summer their fur is brown with lighter brown undersides. Their fur gradually changes to white as winter approaches.

Predators: They are the target of many predators including, bobcat, Canada lynx, coyote, owls, and other birds of prey.

Wikimedia, Nicholas A. Tonelli from Northeast Pennsylvania, USA [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org /licenses/by/2.0)]

Solar panels are a means of gathering energy from the sun that can be converted to electricity. The production of solar panels requires a lot of different mineral resources, which are sourced from many mines around the planet.

Precipitate from clouds, in the form of rain, is an example of the vital transfer of water from one earth system to another in the context of the water cycle.

Maine receives about 42 inches of annual rainfall (about 24 trillion gallons).

Soils are the interface where rocks and minerals (the geosphere), living things (the biosphere), air (atmosphere), and water (the hydrosphere) interact.

They are essential for providing nutrients to plants and are a vital pathway for the transfer of earth materials into the biosphere.

Soils are formed from weathered rock (the parent material) and decomposing organic matter (humus). The parent material determines the texture of the soil. Parent material textures range from gravel (coarsest), through sand and silt, to clay (finest).

Texture and slope of the landscape together determine how well the soil is drained. Due to oxygen in soil, well-drained soil is orange and bright from iron oxide. In contrast, poorly-drained soil at or below the water table is dull or gray.

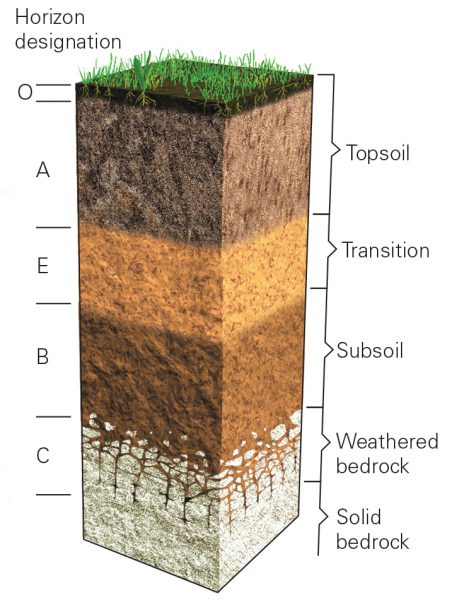

Idealized soil horizon cross section. W.W. Norton image.

As soil develops it forms layers called soil horizons from topsoil to subsoil down to bedrock.

Bedrock is broken down by weathering, which is often aided by plants. As plants grow on Earth materials, they add decayed plant material to make a layer of rich topsoil.

Soil formation is a very slow process, in New England for example, it takes about 100 years to develop an inch of topsoil.

In a place like Maine where soils are well-drained and acidic with a large amount of rain, there is often a light gray (E- horizon) just below a decomposing organic layer. This develops because the minerals in this layer are washed out and deposited creating a bright orange layer below (B-horizon). This is similar to sucking the coloring and flavor out of a popsicle. All that is left is ice.

Can you see the light colored (E-Horizon) near the top of the soil profile shown in the diorama?

Can you see the bright orange B-horizon?

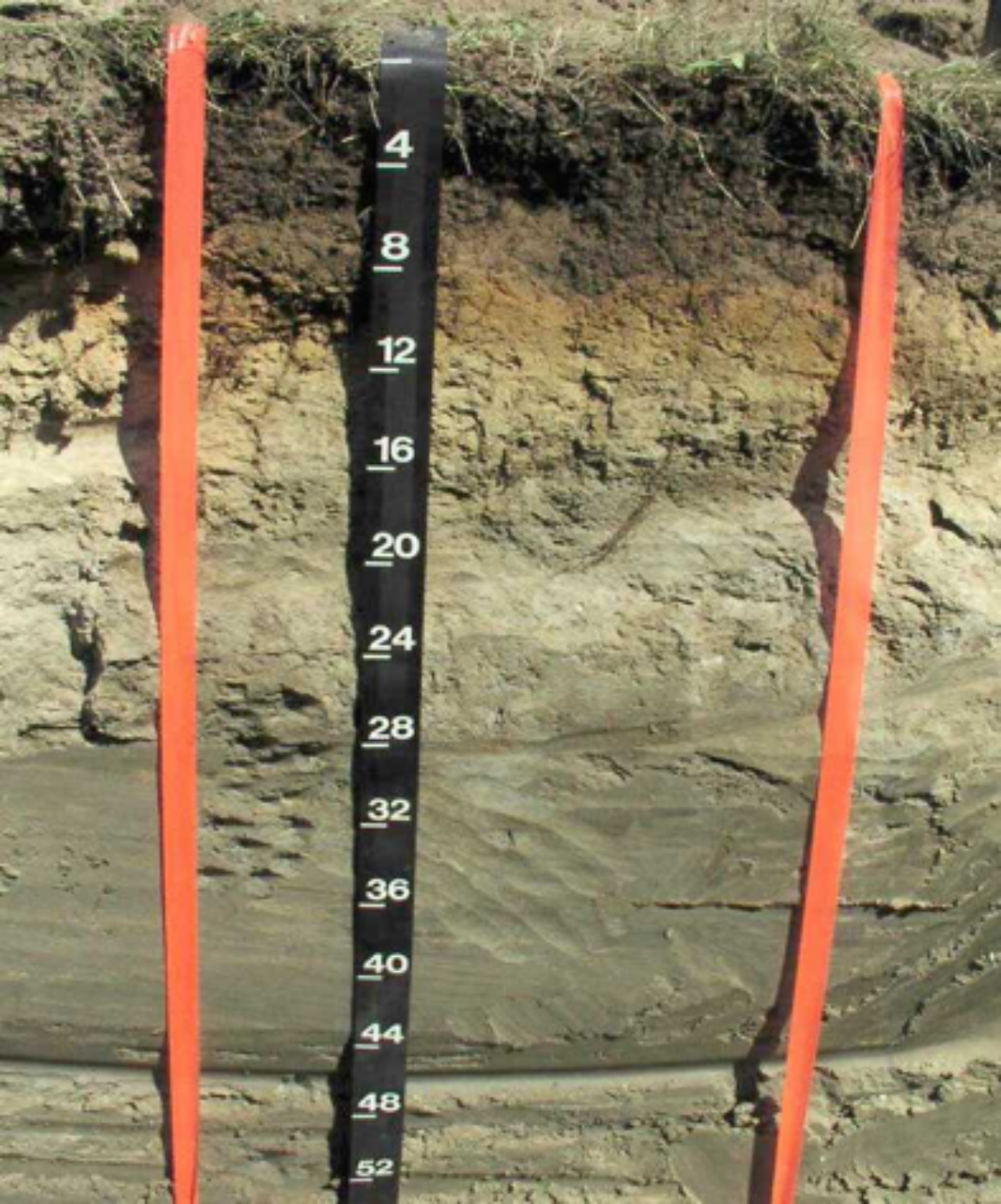

Soil cross section in potato field. Photo courtesy of Christopher Dorion

Soils are a critical part of successful agricultural operations. It is where humans receive the nutrients they need, as these components are taken up from soil into fruits and vegetables.

Soil characteristics are variable. Soil ranges from nutrient-rich to nutrient-poor; dry and well-drained to very wet and poorly drained; and hardpacked clay to lose sand and gravel. These characteristics greatly affect the type of ecosystem that can exist in and on it. This in turn determines how the land can be used.

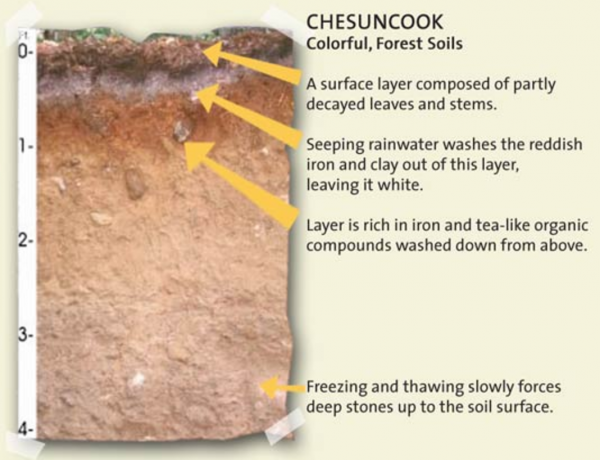

Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

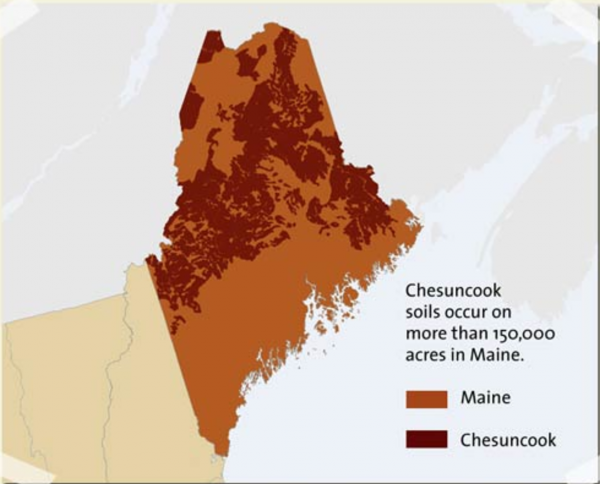

Maine has about 150 distinct and named soil types based on the parent material and drainage class. They provide a strong resource base for its forests and agriculture.

The Maine State Soil is named, Chesuncook, after a village in Piscataquis County. It develops on glacial till. This type of soil is deep, moderately well drained, and consists of a wide range of sediment grain sizes (from boulders to sand). It is found mostly in forested areas of Maine.

Image courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture

Common Name: Balsam Fir

Scientific Name: Abies balsamea

About:

Facts: These trees are frequently found in damp woods

Physical Description:

Leaves: The leaves (needles) are about 1 inch long, dark green, and quite aromatic.

Bark: The bark changes as the tree matures. As a young tree, the bark is pale gray with noticeable blisters, filled with sap. As the tree matures the bark becomes rough with vertical cracks as the blisters are no longer present. It takes on a brownish color.

Cones: Like other conifers, the appearance of cones change with maturity. The balsam fir cones begin with a dark purplish-green color and mature to a light brown. The cones grow in an upright fashion.

Uses: Balsam fir trees are used for lumber, pulp, and its leaves are commonly sold as aromatic décor. It is also the favored species for use as a Christmas tree.

Balsam fir is the most abundant tree in the state of Maine.

Distribution of balsam fir in North America. Image courtesy of Elbert L. Little, Jr., U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service

Tree roots splitting boulder.

Tree roots are as important as the trunk, branches, and leaves above the ground. Roots anchor the tree in place and bring water and nutrients to the rest of the tree.

In many cases the roots of trees interact with mycorrhizae fungi to greatly increase the uptake of water and nutrients. Oftentimes the roots of individual trees compete for water and nutrients. Yet sometimes tree roots also exchange nutrients and chemical messages with one another. Sometimes trees of a single species become interconnected by a large root network that functions as a single organism.

Roots weather rocks by breaking them down into smaller fragments. They also assist in the development of soil by adding organic matter to the ground. Tree roots play a critical role in stabilizing sediment and soil. Their complex network of roots holds these materials in place preventing erosion.

Gravel bar in the Sunday River. Photo courtesy of Maine Geological Survey.

Streams and rivers are very active environments, both geologically and biologically. The path of a river or stream is determined by the local geology (bedrock and surficial sediments) and the topography of the region.

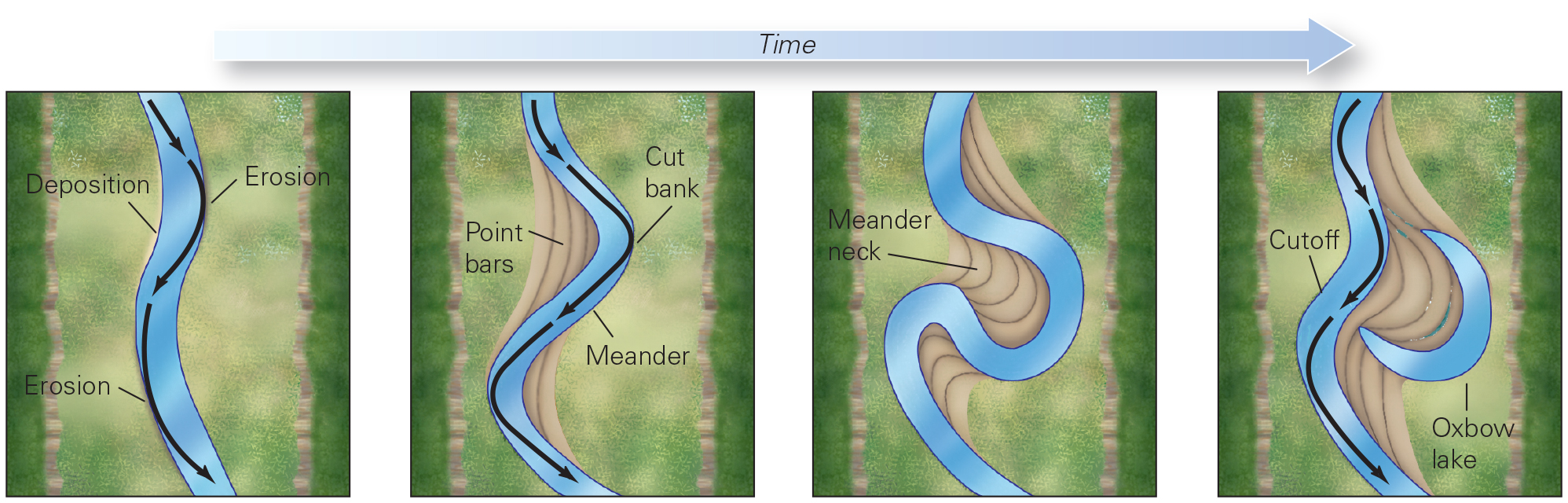

The shape of a river channel is constantly changing. Turbulent, flowing water erodes the sides of channels and over time creates winding S-shaped patterns. These are called meanders and are commonly seen in the low-lying regions.

The outer edge of these meanders or curves, called a cut-bank, is steep from erosion. The water in this part of the channel is deep and faster moving. The inside of the edge of the curve is generally shallow and the current moves slowly. Deposits of sand and gravel found here are called gravel-bars.

Evolution of a meandering stream. W.W. Norton image.

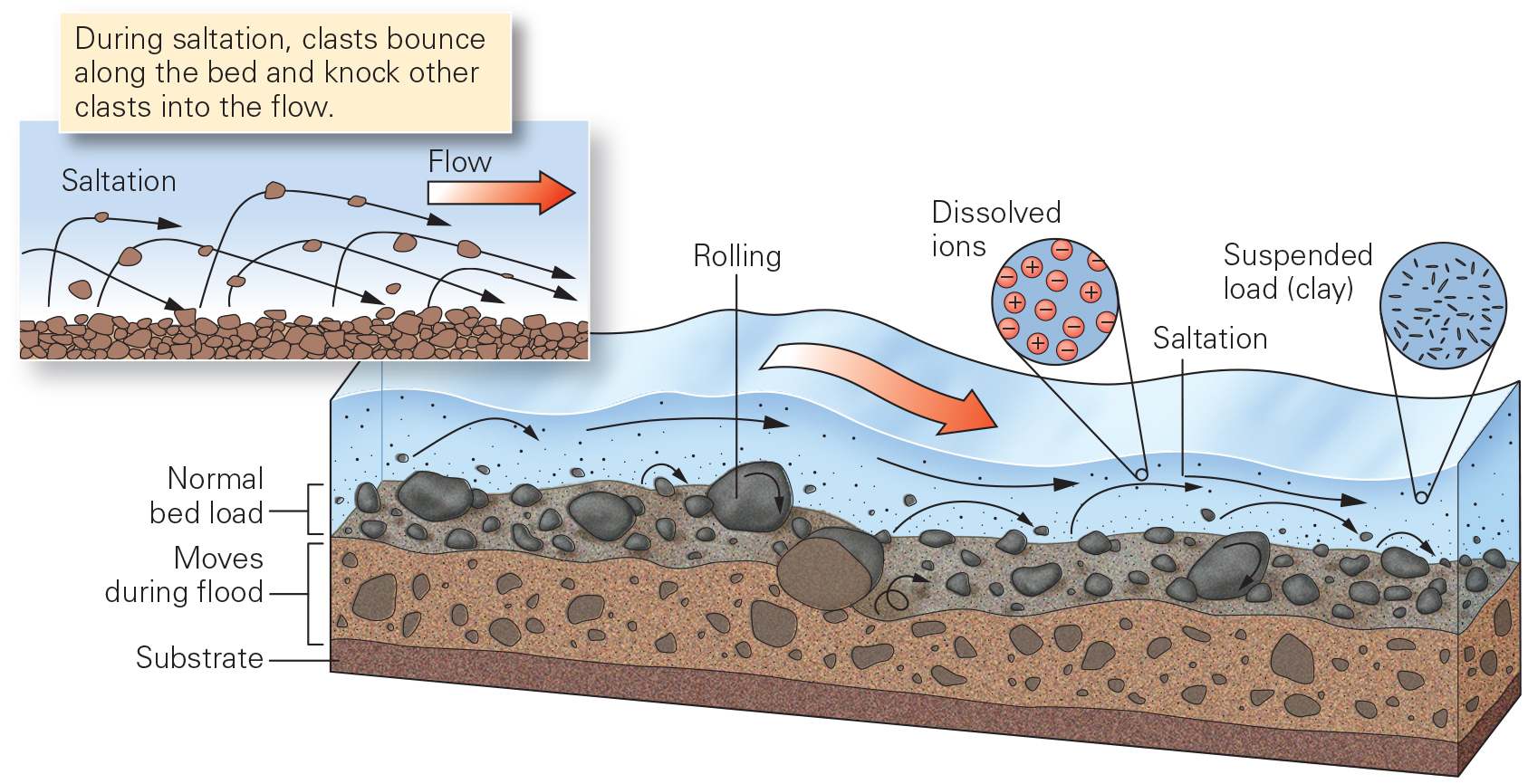

Flowing water can move tremendous amounts of material, called the load, across the landscape. There are several ways that sediment is carried by flowing water. These are dependent on the velocity of the flowing water and the size of the sediment grains– sand, pebbles and even boulders. Smaller sediment grains remain suspended in the flowing water, whereas larger grains can bounce (saltation), drag or roll along the stream bed. Some minerals may dissolve in the water.

Different ways in which sediment is transported in flowing stream water. W.W. Norton image.

Rivers and streams create diverse habitats. A wide range of plant and animal species live and feed within and beside streams.

Aquatic insects, amphibians, fish and snails are some of the common types of organism found in streams. Many primary and secondary consumers use streams and rivers as a source for food including reptiles, birds, and mammals. The margins of streams and rivers are a special habitat where moisture-loving (hydrophilic) plants abound.

Rocks found in stream beds are normally smooth and rounded. Why does this happen? As sediment particles travel down a flowing river channel, they collide with one another. This action breaks off the corners and edges of these grains causing them to become more rounded. Rocks become smooth as sand grains in the flowing water are pelted against the rock surfaces.

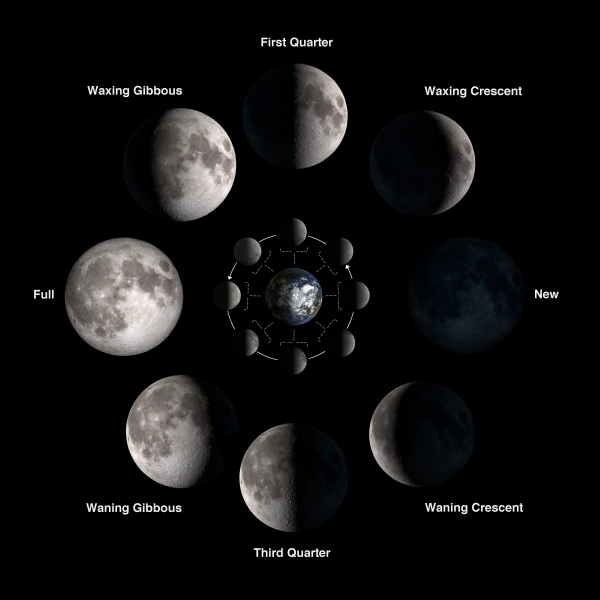

Every night the moon looks a little different. There are nights when we see the entire surface, other times it appears to be absent. At times only segments of the moon are visibly lit, and the shapes of these lit portions change throughout a month time.

Why does this happen?

The shape of the lit portion of the Moon varies as the Moon rotates around the Earth in a 28 day cycle. The position of the Moon in relation to the Sun and Earth will cause these shapes to change. If the Moon is between the Sun and Earth it will barely appear in the sky. If Earth is positioned between the Sun and the Moon, the Moon will appear fully lit. The moon will be partially lit at any position in between.

There are eight primary phases of the moon named: New, Waxing Crescent, First Quarter, Waxing Gibbous, Full, Waning Gibbous, Third Quarter, and Waning.

Phases of the moon. Image courtesy of NASA.

The Moon and Sun cause some of the highest tides in Maine’s

waters. When there is a new moon, the Sun and Moon pull in the same direction. Tides are higher because the gravity from the Moon and Sun are working together. When there is a full moon, the Sun and Moon are on opposite sides of the Earth. During the other phases of the Moon, the Sun and Moon do not line up and the tides are not as high or low.

Winter green protruding from fallen leaves on forest floor. Photo by Jennifer Cote.

Leaves that fall from trees will eventually decompose and reintroduce nutrients to the soil.

They help form the rich topsoil layer in woodlands. Decomposers, such as fungi, bacteria, protozoans, and scavengers are a major way that materials get recycled in the environment.

mycelium with conidiophores on leaves. Petr Kapitola, Central Institute for Supervising and Testing in Agriculture, Bugwood.org

Bunchberry in bloom. Photo courtesy of Bugwood.org.

Ground cover vegetation helps protect soil from erosion. By preventing this process, soil nutrients, organic matter, and sediment remain in place. Various species of groundcover often serve as food for wildlife.

Ferns, a good example of ground cover, are an indication of wet areas in an environment. They are commonly found in valleys and low-lying areas where soils are poorly drained and water can accumulate.

Some common ground covers found in Maine forests include: wild blueberry, wintergreen, and bunchberry.

Ponds, lakes, and wetlands play a major role in the freshwater environment. They are a major ecosystem in Maine and provide a very productive habitat for organisms.

© Ian Patterson, courtesy The Nature Conservancy.

Ponds, lakes, and wetlands are influenced by Maine’s geology and past geological processes. Glaciers melted from Maine about 12,000 years ago. Many of the lowland areas in Maine were formed from glaciation, either from the carved bedrock or the sediments they have left behind. These lowland areas later filled in with water. Wetlands form along the edges of ponds and lakes. Some wetlands form in “kettle hole ponds” created by large chunks of ice that were left by the glacier and then melted leaving a depression in the sediment for water to be stored.

Wetlands have specific plants and animals that are adapted to poorly drained soils such as “bullfrogs, turtles, blue herons, osprey, mink, beaver, deer, moose, snowshoe hare, tamarack, winterberry, ferns, sedges, rushes and grasses,” according to the Maine Department of Environmental Protection. Also, wetland soils are often quite acid, that ties up the nutrients in the soil. Some wetland plants, such as pitcher plants, sundews, and bladderwort, are carnivorous. They catch insects for additional nutrients.

Water stored in wetlands is released slowly into the environment. This helps prevent flooding and helps provide water to surrounding areas throughout the year. Many agricultural operations rely on surface water to irrigate crops or provide water to livestock.

Howard F. Schwartz, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org

Robert Vidéki, Doronicum Kft., Bugwood.org

Apple orchards and wild apple trees play an important part in Maine’s economy and environment. According to the Maine Department of Agriculture, “36.3 million pounds of apples were harvested in 2016, with a total value of $17.5 million.” Apart from human consumption, apples are an important food source for many different species of birds and insects, as well as deer, moose, and bear.

Because climate conditions are crucial for success, the slope of the land and well-drained soils are important for growing apple trees. Apples need 6-8 hours of full sun. The slope and orientation of the land can determine the amount of sunlight and whether frost will damage the blossoms when they are flowering. Apples do not like soil that is too sandy because it dries too quickly and does not hold nutrients well. Wet soils containing too much clay can also discourage growth.

Like many species of flowering plants, apples require pollinators to produce fruits. During May, when apples are coming into bloom, beehives are a common feature found in many orchards across the state of Maine. These insects work tirelessly during the warm and dry days to collect and spread pollen to fertilize the trees. Bee species and other types of pollinators are critical to the growth of apples and most fruits and vegetables.

Swallowtail butterfly. Becca MacDonald, Sault College, Bugwood.or

There are 200 species of moths and butterflies in Maine. They have adapted to the environment in many different ways.

One of the most amazing aspects of moths and butterflies is that they go through a complete change in their life from a caterpillar to a winged organism. Both kinds of insects go through a four-stage life cycle from an egg to larvae (a caterpillar), followed by a pupae stage (cocoons for moths and chrysalis for butterflies.) in which they make a final complete change in form into winged moths and butterflies. This process is known as complete metamorphosis.

Other insects also go through a series of stages but since each stage looks like a miniature of the previous stage it is known as incomplete metamorphosis. Grasshoppers are an example of an insect that undergoes an incomplete metamorphosis.

Oftentimes moths and butterflies, and their larvae equivalents, live off the nectar and leaves of specific plants. In this way, the kinds of soils and other environmental conditions help determine where each kind of moth or butterfly will reside.

Many butterflies and moths help pollinate different flowers.

Moths tend to be active in the night where butterflies are active in the day.

Moths and butterflies have many different adaptations that help them survive in different conditions.

Decomposers help return nutrients used by an organism, like a tree, back into the environment.

Moss overgrown stump. Wikimedia Doug Lee / Rotting tree stump in woodland

Examples of decomposers include various bacteria, fungi and lichens, earthworms, insects like millipedes, ants, beetles and their larvae.

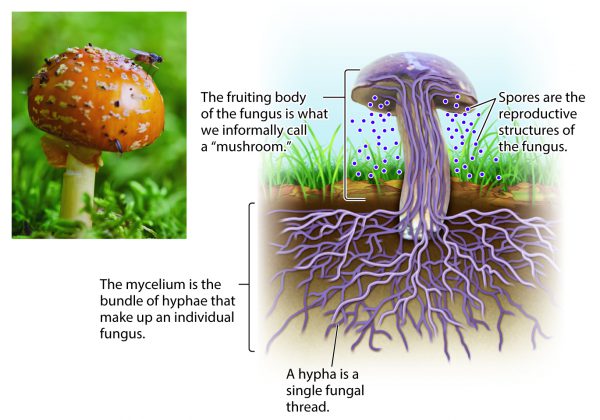

Fungi are the predominant decomposers of plant matter. Many species are found in Maine and different species are attracted to different wood types. Although some trees, such as cedar, decay more slowly than others, the degree of decay a stump exhibits is a qualitative measure of how long ago the forest was logged.

Blueberry flower blossoms. Caleb Slemmons, National Ecological Observatory Network, Bugwood.org

Low bush blueberries are a wild variety of blueberry that grows naturally on an estimated 44,000 acres of Maine land.

They are the state fruit. Though there are several native species here in Maine, the Vaccinium angustifolium, or lowbush blueberry, is the most common. It is the primary species harvested for commercial production.

The plants are low lying shrubs that typically grow up to 8 inches. They flower from May to early June and ripen around August. They prefer well-drained soil that is fairly acidic. They can grow in shaded or semi-shaded areas at varying elevations. Blueberries require insect pollination. Honeybee hives are typically placed in fields for several weeks during the spring. Commercial operations periodically burn the fields to cut down on pests and vegetation, and to fertilize the soil.

Red blueberry fields in the fall.

Caleb Slemmons, National Ecological Observatory Network, Bugwood.org

Havested blueberries. Caleb Slemmons, National Ecological Observatory Network, Bugwood.org

Shelf mushroom in white (paper) birch tree. Photo courtesy of Bugwood.org

Mushrooms are important decomposers.

Like most plants, they make their food. They rely on decaying plant and animal matter for their food source; using enzymes, they extract and concentrate nutrients from the rotting material.

Some species of mushroom native to Maine are edible. Examples include chanterelle (Cantharellus cibarius), chicken of the woods (Laetiporus sulphureus), king boletes (Boletus edulis), and giant puffballs (Calvatie gigantean).

Mushrooms use hyphae (as a group mycelium) to take up their food. Mycelium remain underground all year long, whereas the fruiting body only appears seasonally. The Fruiting body producing and dispersing the spores. W.W. Norton image.

Many of Maine’s mountain tops are used as locations to source wind power. These sites are selected based on the frequency of wind and distance from nearby . The blades are turned by the kinetic energy of the wind. The motion of the blades turns an electric generator that produces electricity. Windmills only produce electricity when they are moving

The manufacturing of windmills require a variety of mineral resources including metal alloys for steel and wiring; rare earth elements and other metal alloys for batteries; and a range of cement products including limestone, crushed stone, sand, and gravel.

Mars Hill Wind Farm, Mars Hill, Aroostook Co., ME. Wikimedia Commons image.

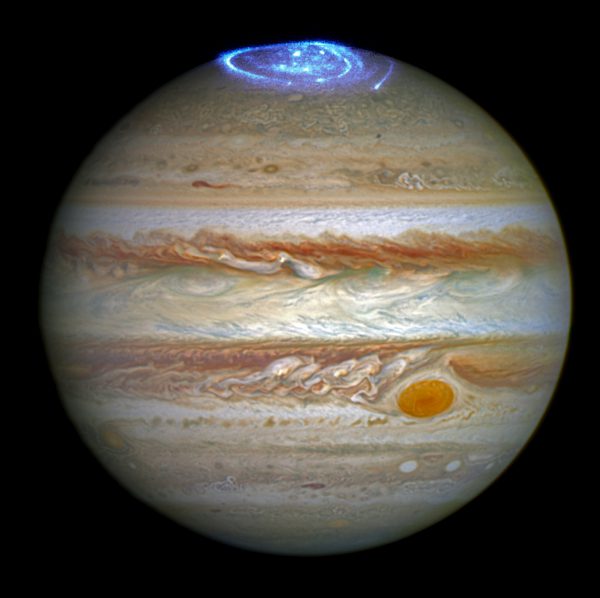

Aurora borealis over Canada seen from the International Space Station. NASA image.

Some of the sun’s energy, in the form of charged particles, may penetrate through Earth’s magnetic field near the North and South poles. The the particles interact with the atmosphere creating the northern and southern lights, aurora borealis and aurora australis, respectively.

Using ultraviolet imaging with the Hubble telescope, NASA captured images of an aurora on Jupiter. NASA image.

Other planets with magnetic fields, like Saturn and Jupiter, also experience auroras.

The Maine State mineral is tourmaline.

Elbaite tourmaline from Havey Quarry, Poland, ME. Photo by Jeff Scovil

Tourmaline is a large mineral group made up of more than twenty-five different species. Only some of these are found in granitic pegmatites. The two most common species found in Maine’s granitic pegmatites are schorl and elbaite. Elbaite is the species that is sought for gem stock.

Tourmaline is one of the principle minerals sought by modern Maine pegmatite miners. Its colors and its transparency are qualities that make it such a desirable gemstone.

Gem tourmaline was first discovered in North America in 1820 in Paris, Maine. It has since been found in several other Maine pegmatites. On February 26th, 1971, the Maine State Legislature designated tourmaline as the Maine State Mineral.

Tourmaline from Maine includes a wide range of colors. See the Hall of Gems exhibit examples of cut stones.

See examples of tourmaline in the Newry, Mt. Mica, Mt. Marie and Maine Minerals A to Z exhibits.

In Maine, the contents of a pegmatite pocket are jumbled together. Crystals are typically found in segments, embedded in a white clay called kaolinite. Extraction of a pocket’s contents is be done carefully to avoid further damage to the crystals.

In Maine, the contents of a pegmatite pocket are jumbled together. Crystals are typically found in segments, embedded in a white clay called kaolinite. Extraction of a pocket’s contents is be done carefully to avoid further damage to the crystals.

Do you see that the bedrock in the diorama is offset? It appears offset along a line, but it is a surface in three dimensions.

This feature (surface) is called a fault and it represents a break in the bedrock along which movement has occurred. Faults are the result of tectonic deformation

Maine’s San Andreas

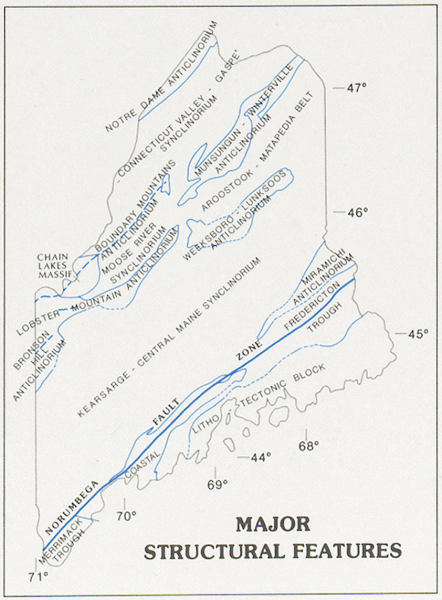

The most well-known fault in the United States is the San Andreas fault in California. At one time, Maine had a long active fault system similar to the San Andreas, called the Norumbega fault system. It runs in a roughly northeast-southwest direction, somewhat west of the coast. No need to worry, the Norumbega fault is inactive.

Map showing the location of major faults in Maine. Note wider, northeast-southwest trending blue line marking the Norumbega Fault system, near coastal Maine. From Osberg and others 1985.

The Norumbega fault was sporadically active for nearly 300 million years, whereas the San Andreas has only been actively for nearly 30 million years. The Norumbega fault is now inactive and has been for millions of years.

To learn more about faults see the plate tectonic module on the tablets

The cylindrical hole and electrical wire are human artifacts – evidence of blasting.

Hard rock is excavated by drilling holes that are loaded with explosives, detonating the explosive, and pushing aside or loading the fractured rock into trucks and removed. A variety of different explosives are used, but the most common variety is dynamite, made from nitroglycerin compounds

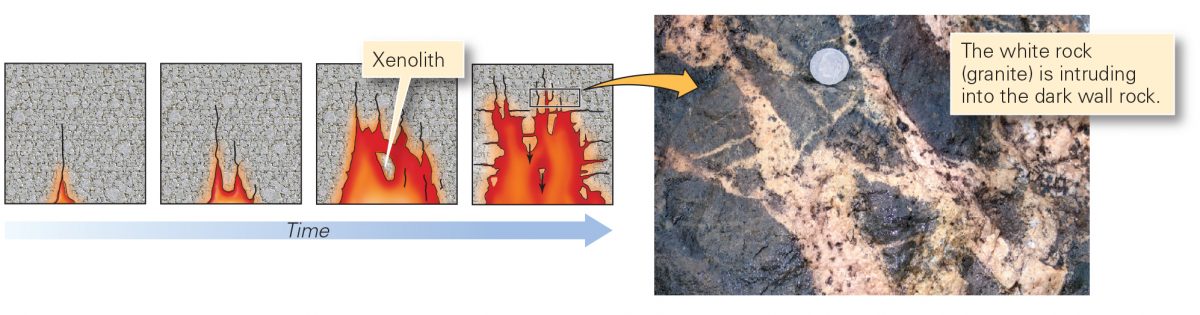

As magma travels through the crust, it may break free pieces of the rock surrounding the melt. A xenolith is a fragment of solid rock that was enveloped in magma before it cooled and crystallized. They are easily recognizable because they do not resemble the rock they are surrounded by.

As molten material travels upward through solid rock, portions of the solid rock become entrapped in the melt. Photo from W.W. Norton

The xenolith in the diorama is a fragment of the metamorphic rock (country rock) surrounding the pegmatite.

Oftentimes a xenolith interacts with the surrounding magma. The entire xenolith, or just a portion of it may melt adding its components into the surrounding magma, a process called assimilation. Sometimes as xenoliths interact with melts, new minerals grow along the margins of the xenolith. In some of Maine’s pegmatites, garnets and schorl are common minerals observed around the margins of xenoliths.

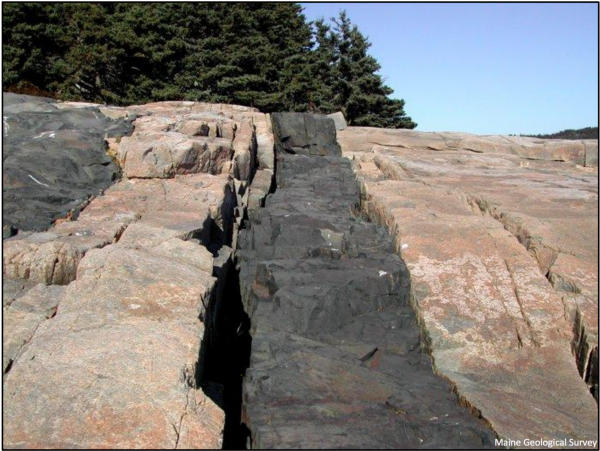

A dike is a relatively thin, vertically or sub-vertically oriented intrusion of igneous rock.

Schoodic Point, Maine Geological Survey photo by Henry Berry.

Dikes of basaltic composition are commonly encountered features in Maine bedrock. Basalt is rich in iron- and magnesium- bearing minerals, which give the rock its dark color.

Like the granitic pegmatite in the diorama, the basaltic dike was originally magma moving through cracks in Earth’s crust. When the magma eventually cooled and crystallized, it took on the shape of the crack to form the dike. Unlike the pegmatite, the mineral grains in the basaltic dike are so small that you need either a hand lens or a thin slice of the rock, in the form of a thin section, to see the individual mineral grains. See the Rock Cycle diagram to your right for an example

In general, the smaller the grain size, the faster the magma cool.

The majority of basaltic dikes found in Maine are probably related to the initial opening of the Atlantic ocean. The break-up of the supercontinent Pangea began in the Mesozoic Era, nearly 250 million years ago. This break-up led to the injection of the basaltic magma from the mantle into the crust. The resulting intrusions are recognized in many parts of Maine as a series of basaltic dikes.

To learn more about Maine’s Geologic History visit the exhibit in the Discovery Gallery.

Pegmatites are very coarse-grained igneous rocks.

The term, pegmatite, is mostly used for coarse, light-colored rocks of granitic composition. Pegmatites are commonly encountered in western and mid-coastal Maine. Pegmatites are sometimes a source of rare and unusual minerals.

Granitic pegmatites are present on every continent on Earth, but make up only a fraction of one percent of all the rocks on Earth.

There are 11 different minerals in the diorama pegmatite. Can you find them?

To learn more about each mineral look at the section Minerals under the heading Geosphere.

Graphic granite is a distinctive intergrowth of quartz and feldspar.

On broken surfaces the gray colored quartz has the appearance of cuneiform writing, hence the name “graphic granite”. It is a texture only observed in granitic pegmatites.

Parallel rods of quartz appear embedded in a single crystal of microcline feldspar. However, these rods are actually part of one single crystal.

When the term Pegmatite was first introduced as a term in the early nineteenth century, it applied specifically to graphic granite.

Graphic granite, Tryon Mountain, Pownal, Cumberland Co., Maine.

Graphic granite, Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscoggin Co., Maine.

Quartz is one of the most abundant minerals in granitic pegmatites. It is commonly found in all parts of a pegmatite and can total up to 30% of a pegmatite. Quartz ranges from small grains, to large masses and even, within pockets, as well-formed crystals.

In Maine pegmatites, quartz comes in colorless, white, brown, black, pink and purple varieties. Explaining the colors of quartz is complicated. Different colors are due to different mechanisms. Brown and black quartz have trace amounts of the element aluminum or while purple and yellow quartz have trace amounts of iron contained within the structure. Rose quartz contains very small inclusions of other minerals. Sometimes quartz and other minerals may be coated with a thin film of minerals that give them color. As an example, iron oxide can give quartz a rusty color

Quartz is a silicate mineral composed of silicon (Si)and oxygen (O2). Its formula is SiO2.

Quartz crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system.

Pure quartz is colorless, but quartz comes in a variety of colors. Thus, color is not a good diagnostic property for identifying it. The colors of quartz include, white, gray, yellow, brown, black, and even pink and purple.

Explaining the colors of quartz is complicated. Different colors are due to different mechanisms. Yellow, brown, purple and black quartz have trace amounts of the elements aluminum (Al) or iron (Fe) contained within the structure. Rose quartz contains very small inclusions of other minerals.

Sometimes quartz and other minerals may be coated with a thin film of minerals that give them color. As an example, iron oxide (Fe2O3) can coat quartz giving it a rusty color.

Quartz breaks with a distinct conchoidal fracture and does not typically display cleavage.

Quartz has a hardness of 7. It will scratch most common minerals. Its density is 2.65 g/cm3, which is average for many minerals and rocks.

Feldspars are also very abundant in granitic pegmatites. The feldspar group includes several chemically different species. The two species found in all granitic pegmatites are the potassium feldspar, microcline, and the sodium feldspar, albite.

The two species commonly found in granitic pegmatites are the potassium feldspar, microcline (KAlSi3O8), and the sodium feldspar, albite (NaAlSi3O8).

Microcline is an economically valuable mineral that was mined exclusively in many of Maine’s pegmatites.

Feldspar loaded into skips waiting to be loaded into truck.

For more information about feldspar mining see the Feldspar Exhibit.

Microcline is the primary feldspar ore from pegmatites.

Microcline comes in a range of colors. Pure microcline is white, but some iron imparts pink to red colors. Green and blue-green is due to trace amounts of lead in the structure.

Examples from Maine pegmatites are commonly white, salmon, tan, orange, and gray. Large microcline crystals are commonly found in the central portions of pegmatites.

Microcline is a species of potassium-rich feldspar. It is a silicate mineral composed of potassium (K), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), and oxygen (O). Its ideal formula is KAlSi3O8.

Microcline crystallizes in the triclinic crystal system.

Microcline comes in a range of different colors. Pure microcline is white, but some iron (Fe) imparts pink to red colors. Green and blue-green is due to trace amounts of lead in the structure. Color alone is not a good diagnostic property for microcline.

Microcline has two pronounced cleavage planes that intersect at nearly 90°. Cleavage is a diagnostic property.

Microcline has a hardness of 6-6.5. It cannot be scratched with a knife blade. Its density is 2.5-2.6 g/cm3.

Cleavelandite is a bladed variety of albite that is found in the interior regions of some pegmatites. The presence of cleavelandite can be an indicator of miarolitic cavities.

Cleavelandite is named after Bowdoin College Professor Parker Cleaveland (1780-1858).

Albite is the sodium-rich end member of the feldspar group. It is a silicate mineral composed of sodium (Na), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), and oxygen (O). Its formula is NaAlSi3O8.

Albite crystallizes in the triclinic crystal system.

Albite is primarily white–for which it is named–and gray, to pale blue.

Albite has two pronounced cleavage planes that intersect at nearly 90°.

Cleavelandite crystallizes in a bladed or platy habit.

Albite has a hardness of 6-6.5. Its density is 2.6- 2.65 g/cm3.

Albite in zoned pegmatites, typically in the interior portion, can develop the pronounced platy crystal habit, known as cleavelandite. It is often white but can sometimes take on a blue color.

Cleavelandite is named after Bowdoin College Professor Parker Cleaveland (1780-1858). The presence of cleavelandite is a good indicator of miarolitic cavities.

IMAGE OF PLATY CLEAVELANDITE HABIT

The mica group includes many different species.

Lepidolite rimmed muscovite crystal. Fisher Quarry, Topsham, ME.

The most common types of mica found in granitic pegmatites are muscovite, ‘biotite’, zinnwaldite, and lepidolite. Muscovite and lepidolite are economically valuable mica minerals.

Muscovite mica was mined from some of Maine’s pegmatites. Lepidolite has been recovered as a bi-product of gemstone mining and is used as a lapidary material.

To learn more about Maine’s mica mining industry and the many uses of mica, see the Mica exhibit.

Muscovite crystals in pegmatite. Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscog

Muscovite mica is a common accessory mineral found in granitic pegmatites.

Muscovite mica is used for a variety of applications including insulators, or as an additive in paints and beauty products.

Muscovite is a silicate mineral composed of potassium (K), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), oxygen (O), and hydroxyl (OH) component. Its complete and ideal formula is KAl2AlSi3O10(OH)2.

Muscovite crystallizes in the monoclinic system.

Muscovite is typically white to silvery gray in color.

Like all mica, muscovite, has perfect basal cleavage. It can be split into paper-thin sheets.

Muscovite has a hardness of 2-2.5. It’s density ranges from 2.76-3.00 g/cm3

Biotite, the common name for dark micas, is a common accessory phase found in granitic pegmatites. Unlike muscovite, biotite mica has little commercial value.

Biotite in pegmatite, Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscoggin Co.

In many of Maine’s pegmatites it is found occurring near the contact between the pegmatite and the country rock.

Biotite is the common name for dark micas. Compositionally they lie in the middle of a field of four end member mica species: annite, eastonite, phlogopite, and siderophyllite. Biotite is a silicate mineral composed of potassium (K), iron (Fe), magnesium (Mg), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), oxygen (O), and a hydroxyl group (OH). It’s formula is K(Fe2+,Mg)3AlSi3O10(OH)2.

Biotite crystallizes in the monoclinic system.

Biotite is commonly black to dark brown in color.

Biotite, like all micas, has perfect basal cleavage.

Biotite has a hardness of 2.5. It’s density ranges from 2.7-3.3 g/cm3.

Lepidolite rimmed muscovite crystal. Fisher Quarry, Topsham, ME.

Lepidolite is a common name for purple or yellow mica found in granitic pegmatites.

It is typically found in the interior portions of some pegmatites. Though it does occur in large sheets, it is commonly encountered in large masses of finer-grained crystals. It is good indicator of nearby gem material because it is often, though not always, associated with gem pockets.

Lepidolite is a silicate mineral composed of potassium (K), lithium (Li), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), oxygen (O), and fluorine (F). The end member formulas are: polylithionite (KLi2AlSi4O10(F,OH2)), and trilithionite (KLi1.5Al1.5AlSi3O10(F,OH)2).

Lepidolite crystallizes in the monoclinic system.

Lepidolite is typically purple but may sometimes be yellow.

Lepidolite, like all micas, has perfect basal cleavage. It often forms large scaly masses but can also form large individual crystals.

Lepidolite has a hardness of 2.5-3. Its density ranges from 2.8-2.9 g/cm3.

Lepidolite (purple) beneath emptied pocket. Havey Quarry, Poland, ME

Common Name: Blue Jay

Rob Hanson from Welland, Ontario, Canada [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by/2.0)]

About:

Habitat: Forests, open fields, and yards where bird feeders might be located

Food: Acorns, nuts, seeds, caterpillars, grasshoppers, and beetles

Physical Description: White or light gray underneath; various shades of blue, black, and white on back, wings, and tail

Habits: Quite social and are commonly found in pairs or groups.

It is the mineral prized by miners for its gem quality and is recovered from open cavities (pockets) though it is also found in the central portions of some pegmatites.

Elbaite tourmaline in quartz. Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscoggin Co.

Elbaite is typically found in pegmatites that contain other lithium-bearing minerals such as lepidolite, spodumene and montebrasite.

Elbaite comes in a range of colors, several colors can often be observed in a single crystal. Colors include green, blue, red, pink, and yellow. It can also be colorless. These colors are given separate varietal names in the gem market, e.g. indicolite (blue), rubellite (red), achroite (colorless).

The most common colors of Maine tourmaline are shades of green and red, where red is the most prized.

See the Hall of Gems exhibit for more example of cut stones.

Elbaite is a borosilicate mineral composed of sodium (Na), lithium (Li), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), boron (B), and hydroxyl (OH). Its ideal formula is Na(Li1.5 Al1.5)3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3(OH).

Elbaite crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system.

Elbaite comes in a range of colors, several colors can often be observed in a single crystal. Colors include green, blue, red, pink, and yellow. It can also be colorless. These colors are given separate varietal names in the gem market, e.g. indicolite (blue), rubellite (red), achroite (colorless).

Elbaite has a conchoidal fracture.

Elbaite has a hardness of 7. Its density ranges from 3.18-3.25 g/cm3.

Schorl in pegmatite, Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscoggin Co.

Schorl is the most common species of tourmaline in Maine pegmatites. It typically occurs through all areas of a pegmatite.

Schorl is black and usually extremely brittle. It is not transparent and therefore is not used as gem material.

Schorl is a borosilicate mineral composed of sodium (Na), iron (Fe), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), boron (B), and hydroxyl (OH). Its formula is NaFe2+3Al6Si6O18(BO3)3(OH)3(OH).

Schorl crystallizes in the trigonal crystal system.

Schorl is black in color.

Schorl is very brittle and has a conchoidal to uneven fracture.

Schorl has a hardness of 7-7.5. Its density ranges from 2.82-3.32 g/cm3

Beryl is a gem material as well as an ore for the extraction of the metal, beryllium.

Beryllium is a metallic element used for manufacturing X-ray equipment and guidance and radar systems. Because it is extremely strong and light-weight, it is also used in space and aeronautics equipment.

Beryllium metal. Image from Wikimedia commons.

The largest beryl crystals found in Maine were from the Bumpus Quarry in Albany Township. Some of these crystals were up to 30 feet in length. At that time, these were some of the largest crystals known in the world.

See the Bumpus exhibit for more on the largest beryl crystals form Maine. See a segment of the largest beryl outside the Museum.

Beryl is a silicate mineral composed of beryllium (Be), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), and oxygen(O). Its formula is Be3Al2Si6O18.

Beryl crystallizes in the hexagonal crystal system. Crystals are commonly tabular or elongated, hexagonal prisms.

Beryl comes in a range of colors including pink, red, blue, green, and yellow. It can also be colorless. These colors are given separate varietal names in the gem market, e.g. morganite (pink), aquamarine (blue to green), heliodor (yellow), and goshenite (colorless). See the Hall of Gems exhibit for examples of faceted beryl.

Beryl has imperfect basal cleavage and tends to exhibit a conchoidal fracture.

Beryl has a hardness of 7.5-8. Its density ranges from 2.63-2.92 g/cm3.

Tin metal. Image from Wikimedia commons.

Cassiterite is generally dark brown or black when found in pegmatites, but it may appear yellow or red in other rock types.

It is often found in the interior portions of pegmatites, commonly associated with cleavelandite.

Cassiterite is the primary ore for the metal tin (Sn).

Cassiterite mineral grains. Image from Wikimedia commons.

Cassiterite is an oxide composed of tin (Sn) and oxygen (O). Its formula is SnO2.

Cassiterite crystallizes in the tetragonal crystal system.

Cassiterite is generally dark brown or black when found in pegmatites, but it may appear yellow or red in other rock types.

Cassiterite is quite brittle and has a sub-conchoidal to uneven fracture.

Cassiterite has a hardness of 6-7. Its density ranges from 6.98-7.1 g/cm3.

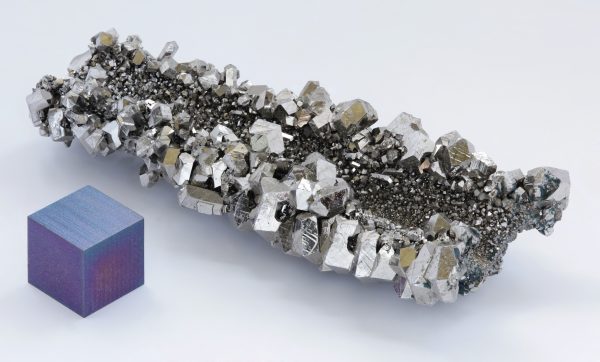

Columbite is an important source of niobium and tantalum.

High grade niobium crystals with 1cm cube. Image from Wikimedia commons.

Columbite is typically found in the interior portion of some pegmatites. The color of columbite is black, however, fractured surfaces often display a bluish iridescence.

Columbite-(Fe), is a niobium oxide composed of iron (Fe), niobium (Nb), and oxygen (O), its ideal formula is FeNb2O6.

Columbite-(Fe) crystallizes in the orthorhombic crystal system.

Columbite-(Fe) is black but surfaces often display a blueish iridescence.

Columbite-(Fe) is a brittle mineral that has a sub-conchoidal fracture.

Columbite-(Fe) has a hardness of 6. It’s density ranges from 5.3-7.3 g/cm3.

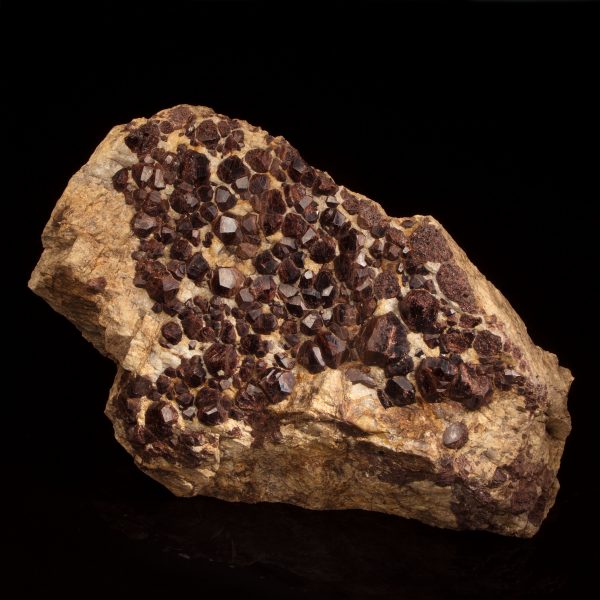

The garnet mineral group consists of many different members with a wide range of compositions.

Red garnet in pegmatite.

The most common species found in granitic pegmatites are iron-rich almandine and manganese-rich spessartine. Almandine is typically red, reddish-brown, or reddish-purple, while spessartine reddish-orange to orange. Almandine is far more common than spessartine.

Almandine is a common accessory mineral in Maine’s pegmatites. At several well-known gem/specimen mines almandine garnet is used by miners as an guide to detect where pockets may be located. The garnets are aligned, creating a layer referred to as the “garnet line”. In some pegmatites, the garnets have a rim of black-blue tourmaline, an indicator that a pocket may be close.

Cluster of garnet crystals in pegmatite.

Do you see a layer of garnets in the diorama?

Almandine is a silicate mineral consisting of iron (Fe), aluminum (Al), silicon (Si), and oxygen (O). Its ideal formula is Fe2+3Al2Si3O12.

Almandine crystallizes in the isometric crystal system.

Almandine is typically red, reddish-brown, reddish-purple, or reddish-orange.

Almandine has no cleavage and fractures conchoidally.

Almandine has a hardness of 7-7.5. Its density is 4.05 g/cm3.

The pegmatite (white) extends from left to right in the image. Above it is the brown, rusty-colored rock it intruded, simply called “country rock”.

The term “country rock” is commonly used as a generic term to describe the rock surrounding a pegmatite (or any intrusive rock for that matter). In this way, the actual rock type is not described but distinguished as separate from the pegmatite.

Note the layers in the metamorphic rocks surrounding the pegmatite. The layers were not always folded. They were originally flat but were compressed and contorted by surrounding tectonic forces. These forces produced the folds seen in the rock. The majority of Maine’s bedrock is metamorphic and those rocks are commonly folded, though the scale of the folds varies.

For more information on Rocks see Rocks in the Geosphere section on the tablets.

Folded metamorphic rock. Courtesy of the Maine Geological Survey, David West photo.

Finding pockets in pegmatites is an acquired skill. Miners commonly use the presence of specific minerals, “indicator minerals,” as a means to detect the pockets.

Purple lepidolite at base of pocket, Havey Quarry, Poland, Androscoggin Co.

Inside the pocket, green elbaite crystals protrude from bulbous cleavelandite masses along the bottom. The ceiling of the pocket is lined with smoky quartz crystals.

The pegmatite in the diorama exhibits a mineral association that is common in some of Maine’s tourmaline-bearing pegmatites. Minerals associated with pockets in this type of pegmatite include pink and green elbaite tourmaline, large microcline feldspar crystals, and large pods of lepidolite and quartz.

This undiscovered pocket in the diorama represents our interpretation of what an undisturbed pocket would look like after it had fully cooled and crystallized. We base this interpretation on evidence found in the field from pegmatites in Maine and worldwide. Pristine pockets resembling this one are rarely encountered in Maine pegmatites. Due to various outside forces, such as plate tectonic processes, the pocket contents tend to become broken and jumbled. The contents may include clay (a weathering product of the feldspar), and often rust or other oxide minerals cover the surfaces of minerals found in the pocket.

Pegmatite miners use a variety of tools to extract desired minerals from the pegmatite.

Detonation wires on quarry wall left behind after a blast.

Heavy-duty equipment such as drills and compressors, and excavators aid in the removal of large volumes of rock.

When miners work near pockets, or areas where the desired minerals are present the process becomes more delicate and the tools change. Smaller hammer drills, rock hammers and chisels, or feather and wedge style excavation method may be utilized.

Erratics- How did that rock get here?

“Erratics” are rock fragments that were carried by glaciers some distance from where they originated. They often have no resemblance to the surrounding bedrock. Glacial erratics vary in size ranging from pebbles to house-sized blocks.

The largest glacial erratic in the state of Maine, “Daggett’s Rock”, is located in Phillips. The largest glacial erratic in the country is located in Madison, New Hampshire.

Yellow lichen on marble, Union, Knox Co., ME.

What’s on that rock?

Lichens are a life form that consists of a symbiotic partnership of two separate kinds of organisms, algae, and fungi. These organisms alter the surface of rocks and minerals through biological weathering processes that physically and chemically break down mineral constituents.

The fungal portion of the lichen extracts chemical components from minerals. These components are shared with the algal portion of the lichen. The algae are the photosynthetic partner that provides food for the fungus in the form of carbon. In some instances, nitrogen-fixing bacteria may also be present. These processes are important because they contribute to the development of soils.

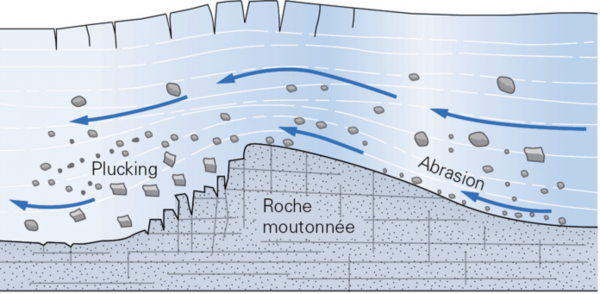

Roche moutonnee in Bethel, ME. Note gradual sloping side on left and steep slop on right. Glacier travelled from right to left in this image. Courtesy of the Maine Geological Survey, photo by Woodrow Thompson.

Have you seen mountains and hills resemble this shape, in Maine?

The shape of the mountain in the mural is common for many of Maine’s mountains. It is an indicator that glaciers once covered the landscape. Twenty thousand years ago Maine was covered with an average of five to ten thousand feet of glacial ice. This distinctive shape is commonly referred to as a roche moutonée. It indicates the direction of glacial movement.

Note the gradual slope on the left and a steep slope on the right. This shape developed as a glacier moved over the top of the mountain. As the flowing glacier rode over the left side of the mountain, it ground down on the bedrock creating a gentle slope. As it continued moving over the right end of the mountain, it began removing, “plucking”, bedrock creating a steep cliff face.

Though these features are found in many areas in Maine, some of the best-known examples are “The Bubbles” in Acadia National Park and Mt. Kineo in the Moosehead Lake area.

Mount Kineo, photo courtesy of Maine Bureau of Parks and Lands

In the diorama there is a sharp boundary separating the pegmatite and the surrounding metamorphic rock (the country rock), this boundary is called a contact.

Pegmatite (white) and metamorphic rock (dark) contact. Mt. Apatite, Auburn, ME

Recognizing contacts is important in geology because they allow a geologist to establish the sequence of events that led to the formation of the outcrop

Without knowing the exact time that this all happened, geologists have established that metamorphic rocks formed first, then were later intruded by the pegmatite melt, a separate event.

Is there another example in the diorama where you see one rock type cross cutting another?

How many separate events occurred in this diorama outcrop?

Basaltic dike (vertical), cross-cutting pegmatite (white, below) and metamorphic rock (dark, above). Haye Quarry, Poland, ME

Shooting stars are not actually stars. They represent meteors, stony or metallic material that have entered Earth’s atmosphere.

Perseid meteor descending into Earth’s atmosphere. Photo courtesy of NASA

Upon entering the atmosphere meteors burn due to friction, producing the streaks of light in the sky. Most meteors burn up before reaching the ground. Sometimes enough of the material withstands entry and reaches the surface of Earth to become a meteorite.

Meteor showers occur annually when Earth’s orbit passes through regions of the solar system that have a concentration of debris. Comets often shed debris behind them as they orbit the sun. Meteorite showers are named after the constellations from which they appear to originate.

Some examples of the annual, major meteor showers are listed below. The time ranges show when they may occur. However, these are subject to change.

Quadrantids- Early January

Lyrids- Mid to late April

eta Aquarids- Late April to early May

Southern delta Aquarids- Mid July to Mid August

Perseids- Late July through August

Orionids- Late September to late October

Leonids- Mid November

Geminids- Early to mid December

Ursids- Mid to Late Demember

Learn more about Meteorites in the Space Rocks Gallery

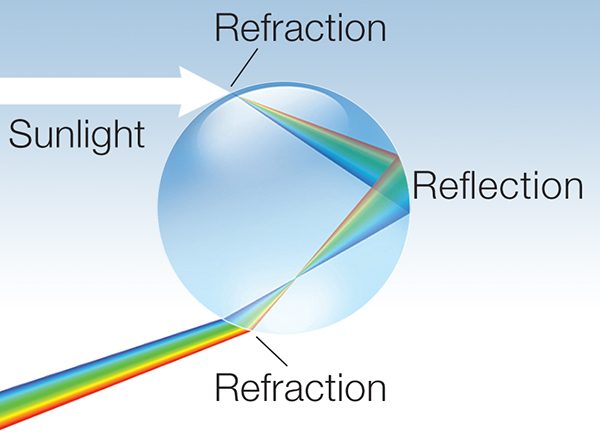

Rainbows are a natural phenomenon which occur when sunlight and rain interact.

Sunlights interaction with a water droplet. Photo courtesy of the Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology.

Light enters into a raindrop and is refracted, which disperses the light into different wavelengths (red through violet colors). Some of these wavelengths are reflected off the back of raindrops and come back out of the raindrop displaying a rainbow

Rainbows can be observed whenever water droplets are present in the air and the Sun is positioned at a low angle. An individual will be able to see the rainbow if he or she is standing between the water droplets and the Sun.